2

The recent history of tech is littered with post-digital Mechanical Turks: whether its Elizabeth Holmes selling a blood testing ‘lab in a box’ while behind the scenes most of the tests were conducted by traditional machines and human technicians, Builder.ai offering autonomous software development that was just hundreds of software engineers instructed to mimic the appearance of AI, or Watney robotics, a startup that arbitrages the cost of labour to hire workers in the global south as 24/7 ‘tele-operators’ for laundry folding robots. Though some of these cases are outright fraud of perceived automation, others have (in the most cynical tone possible) been more transparent about the worker behind the robot. To Silicon Valley it seems, The Mechanical Turk is not a metaphor for technological fraud but a savvy business model for using cheap labor to maximize value without the hassle of real innovation. Humanity is stuffed into the machine, hidden behind a facade of cogs and levers, subsumed into the wood and metal to become a speculative asset for the next hype cycle.

In this modern re-envisioning of the Mechanical Turk, technology becomes a means of social order and control. In her lectures ‘The Real World of Technology’, scientist Ursula Franklin, referred to these systems as prescriptive technologies: the division of labour into discrete steps, with each worker working to a specific plan, rather than the holistic craftsperson creating an object from start to finish. This methodology allows increasingly less agency to be exerted within any given stage of production. To engage with this technology the both the worker is required to act more and more as a machine — Franklin argues ‘prescriptive technologies eliminate the occasions for decision-making and judgement in general and especially for the making of principled decisions’. The implementation of prescriptive technologies sacrifice agency in favour of efficiency and discourage a holistic understanding of their function.

The division of labour in a post-digital Mechanical Turk justifies inequality by promising a future of automation without meaningfully investing in its development. Speculative markets value the promises made by technologists more than the present-day reality of their technology, and so are willing to accept Mechanical Turks as ‘innovation’ regardless of the labour involved behind the scenes. The workers presently contained within the machine now exist within an ecosystem that already imagines them as automatons, devaluing the very labour that makes the technology function. It’s not automation, it’s just puppetry. Technocrats like Musk can then gather the capital necessary to make everyone buy into the technology without ever needing to prove that it’s possible without the significant human cost.

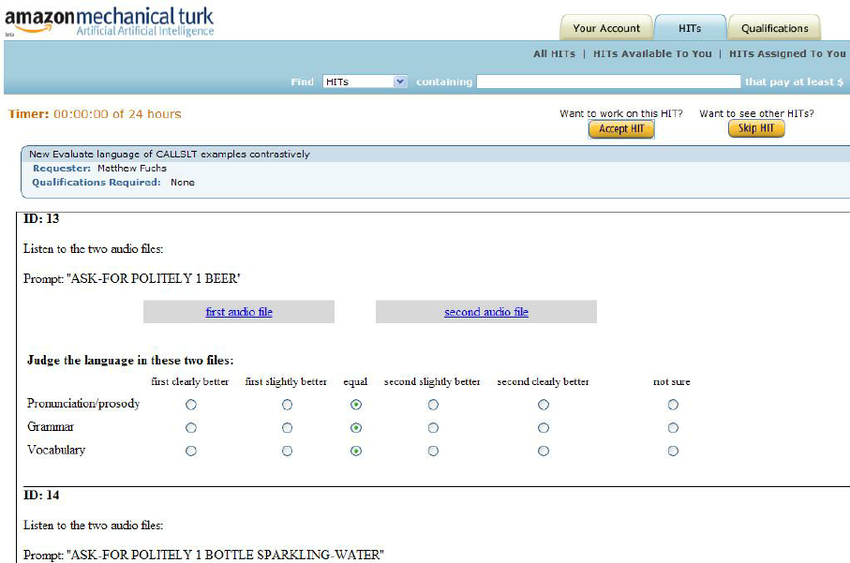

Perhaps the most widely known and successful of these post-digital Turks is also the most brazen: Amazon’s eponymously titled labour sourcing platform, Mechanical Turk. Launched in 2005, Amazon’s Mechanical Turk presented a digital marketplace for freelance micro-work, where companies (‘Requesters’) advertise tasks for human workers (‘Turkers’) that computers could not yet perform: tagging images, transcribing audio, completing surveys, or moderating content to name a few. Amazon’s decision to name its labour outsourcing system Mechanical Turk could be seen as a cynical act of transparency, but it also signalled a social shift in the ways in which tech platforms would see and interact with workers. It didn't matter if your task was not yet able to be automated—with a few simple API calls there was always a ready pool of labour that you could pull from, the worker imperceptible within the machine.

Of course Amazon itself would eventually become guilty of using these workers in exactly the manner they named them. In early 2024 it was revealed that much of the automation contained in Amazon’s short lived ‘Just Walk Out’ grocery stores, was in fact manually logged and tagged by Amazon Mechanical Turk workers predominantly based in India. Although this was widely mocked as a failure when it was revealed, Amazon barely flinched. They viewed the model a success even if its only innovation was simply moving the labour costs of a grocery store to a location with less regulatory oversight and much lower wages.

...‘the political decisions related to the advancement of technology and the provision of appropriate infrastructures are made on a technical level, far away from public scrutiny. But these decisions do incorporate political biases... which, in a technical setting, need not be articulated. As far as the public is concerned, [the] decision, and its often hidden political agenda, becomes evident only when the plans and designs are executed and in use. Of course, at this point change becomes almost impossible.’ - Ursula Franklin

As with the Mechanical Turk which hides labour behind a false veil of automation, the trimmings of technology provide a Trojan horse for corporations who wish to politically realign the world, increase their power and decrease the agency of workers. This technological misdirection is as violent in intention as any other corporate strikebreaking or union-busting initiative, it just arrives packaged in a software update.